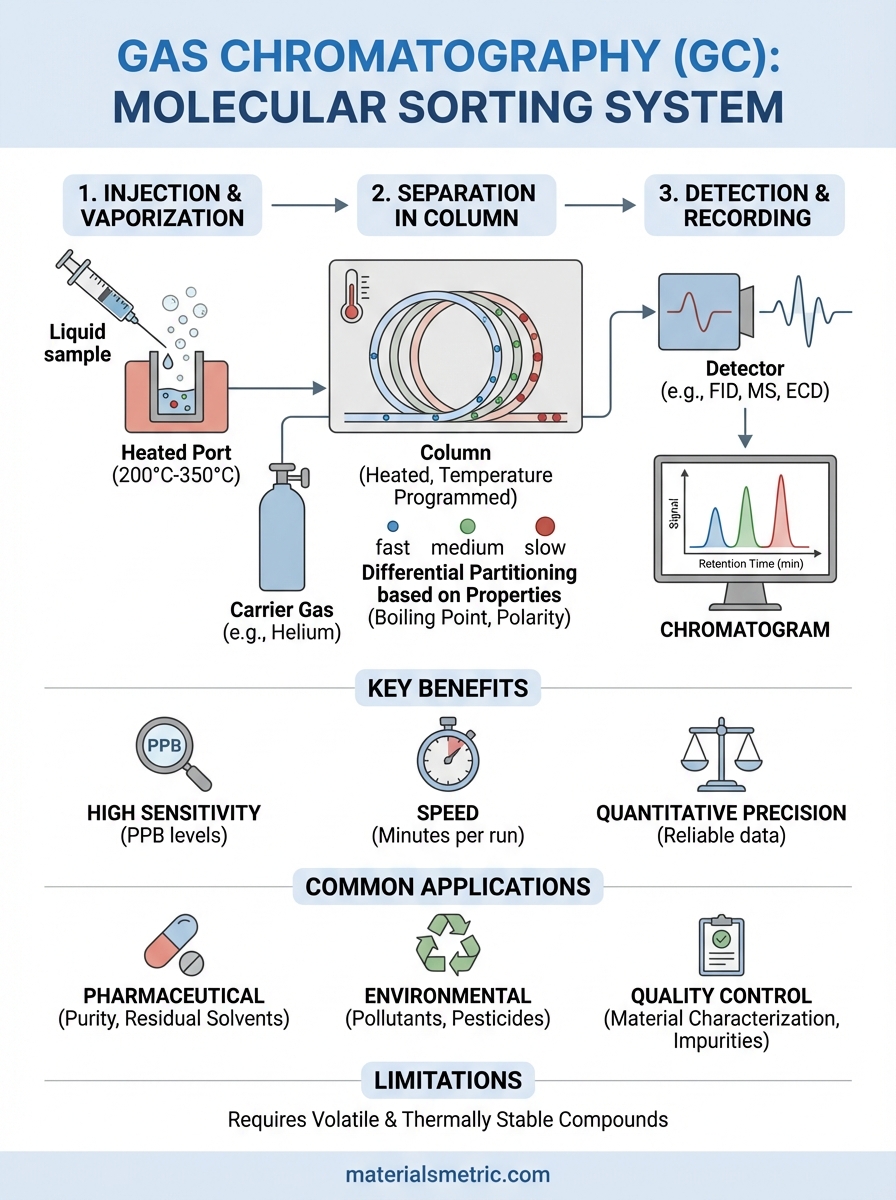

Gas chromatography (GC) is an analytical technique that separates and identifies chemical compounds in complex mixtures. Think of it as a molecular sorting system. You inject a sample into the instrument, heat it until it vaporizes, then watch as an inert carrier gas pushes those vaporized molecules through a specialized column. Different compounds travel through that column at different speeds based on their physical and chemical properties. As each compound exits the column, a detector measures its presence and quantity. The result is a chromatogram showing distinct peaks for each component, which you can use to identify and quantify what’s in your sample.

This article walks you through everything you need to understand gas chromatography. You’ll learn why it matters for materials characterization and quality control, how to use it effectively, and what makes the technique work at a fundamental level. We’ll break down the main system components, show you real applications across industries, and cover the advantages, limitations, and common troubleshooting scenarios you might encounter. Whether you’re evaluating a new analytical method or need to understand GC data, you’ll finish with a solid foundation.

Why gas chromatography matters

Gas chromatography delivers analytical precision that directly impacts your product quality, regulatory compliance, and bottom line. When you need to detect trace impurities in pharmaceutical formulations, verify material purity in manufacturing processes, or identify contaminants in environmental samples, GC provides quantitative data you can trust. This technique separates complex mixtures into individual components with resolution that other methods struggle to match, giving you the detailed chemical fingerprint necessary for informed decisions about materials, processes, and products.

Detection sensitivity that drives quality decisions

Understanding what is gas chromatography reveals why sensitivity matters so much in your work. Modern GC systems detect compounds at parts-per-billion concentrations, making them essential when you need to catch contaminants before they cause product failures or regulatory issues. You can identify specific volatile organic compounds in medical device materials, trace residual solvents in drug substances, or pinpoint impurities that affect material performance. This detection capability transforms abstract quality concerns into measurable, actionable data that protects your reputation and ensures patient safety in biomedical applications.

"The ability to quantify components at extremely low concentrations separates gas chromatography from many other analytical techniques."

Speed and cost advantages in real workflows

Your laboratory faces constant pressure to deliver results faster while controlling costs. GC analysis typically completes in minutes rather than hours, allowing you to make decisions without waiting days for external lab reports. You run multiple samples per day using standardized methods, which reduces per-sample costs compared to techniques requiring extensive sample preparation or expensive consumables. This efficiency matters when you’re troubleshooting production issues, screening material batches, or supporting time-sensitive development timelines where delays cost money and competitive advantage.

How to use gas chromatography in practice

Understanding what is gas chromatography extends beyond theory into practical application that requires attention to detail at every step. You start by preparing your sample correctly, selecting appropriate operating conditions, and interpreting the resulting data. The process follows a systematic workflow that balances accuracy with efficiency, whether you’re analyzing pharmaceutical compounds, environmental samples, or materials for quality control. Your success depends on making informed choices about sample preparation, column selection, carrier gas flow rates, and detector settings.

Sample preparation fundamentals

Your analysis begins with proper sample preparation, which directly affects the quality of your results. You need samples in a form that vaporizes cleanly without decomposing, which means volatile or semi-volatile compounds work best. For liquid samples, you typically dissolve them in an appropriate solvent and inject microliter volumes directly into the system. Solid samples require dissolution or headspace sampling techniques that capture volatile components above the sample. Clean samples matter because contaminants can damage your column or produce interfering peaks that complicate interpretation.

Derivatization transforms difficult compounds into GC-compatible forms when you’re dealing with polar or thermally unstable materials. This chemical modification process increases volatility and improves peak shape for compounds like fatty acids, amino acids, or compounds containing hydroxyl or carboxyl groups. You add a derivatizing reagent that reacts with functional groups, creating more stable derivatives that travel through the column without degradation. The technique expands your analytical capabilities but requires method development time to optimize reaction conditions and ensure complete conversion.

Running the analysis

You inject your prepared sample through a heated inlet port where instant vaporization occurs, typically at temperatures between 200°C and 300°C depending on your compounds. The carrier gas (helium, nitrogen, or hydrogen) sweeps vaporized molecules into the column where separation happens. You control the column temperature using programmed heating ramps that start low for volatile compounds and increase gradually to elute higher-boiling components. This temperature programming prevents peak overlap while keeping analysis times reasonable.

"Temperature control throughout the injection port, column, and detector determines separation quality and peak resolution."

Monitor your chromatogram as it develops in real time, watching for peak shapes and retention times that match your standards. Integration software calculates peak areas and compares them to calibration curves you’ve built using known concentrations. You verify system suitability by running quality control samples between unknowns, checking that retention times remain stable and peak resolutions meet acceptance criteria. Document all operating parameters because reproducibility requires consistent conditions across runs and between instruments.

Core principles of gas chromatography

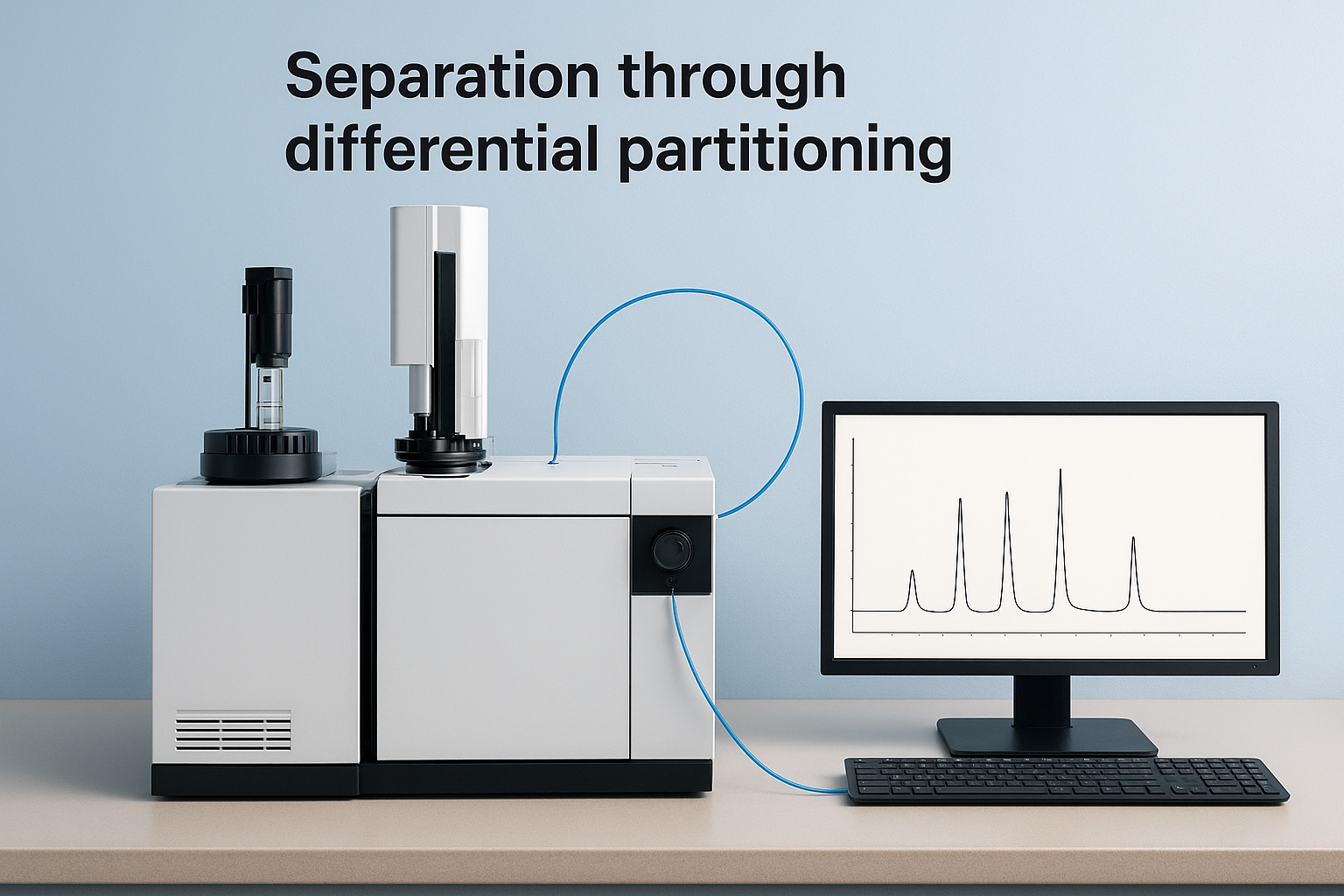

Gas chromatography works by exploiting physical and chemical differences between compounds in a mixture. You inject a sample into a heated system where it vaporizes, then an inert carrier gas pushes those molecules through a column containing a stationary phase. Each compound interacts differently with that stationary phase based on its molecular properties, creating separation as compounds travel through the column at unique speeds. The compounds that interact weakly with the stationary phase move quickly, while those with stronger interactions take longer to exit. This differential movement creates distinct peaks on your chromatogram that represent individual components.

Separation through differential partitioning

Your separation quality depends on partitioning behavior between the mobile gas phase and the stationary liquid or solid phase inside the column. Compounds constantly move between these two phases as they travel through the column. When a molecule dissolves into the stationary phase, it stops moving forward temporarily. When it returns to the mobile gas phase, the carrier gas pushes it forward again. This continuous exchange happens thousands of times per second, creating the separation you observe.

Molecular characteristics determine how compounds partition between phases. Boiling point represents the primary factor, with lower-boiling compounds spending more time in the gas phase and eluting faster. Polarity also matters because compounds interact more strongly with stationary phases of similar polarity, which slows their progress. Your column temperature directly affects these interactions, with higher temperatures increasing vapor pressure and reducing stationary phase retention. This explains why temperature programming works so effectively for mixtures containing both volatile and less volatile compounds.

"Separation occurs because different molecules spend different amounts of time dissolved in the stationary phase versus traveling in the mobile gas phase."

Temperature and retention time relationships

Understanding what is gas chromatography requires grasping how temperature control shapes your results. You set the column temperature based on the boiling points of your target compounds, knowing that components elute when they achieve sufficient vapor pressure to remain primarily in the gas phase. Isothermal methods maintain constant temperature throughout the run, which works well for narrow boiling point ranges but causes problems with complex mixtures. Low temperatures retain high-boiling compounds too long, creating broad peaks. High temperatures rush low-boiling compounds through without adequate separation.

Temperature programming solves this problem by starting at lower temperatures to separate volatile compounds, then gradually increasing temperature to elute higher-boiling materials. You design temperature ramps that balance resolution against analysis time, typically using rates between 5°C and 20°C per minute depending on your separation needs. Retention time becomes your primary identification tool because compounds elute consistently at specific times under controlled conditions. You compare retention times from unknown samples against authenticated standards, using relative retention times to confirm component identity even when absolute retention times shift slightly between runs.

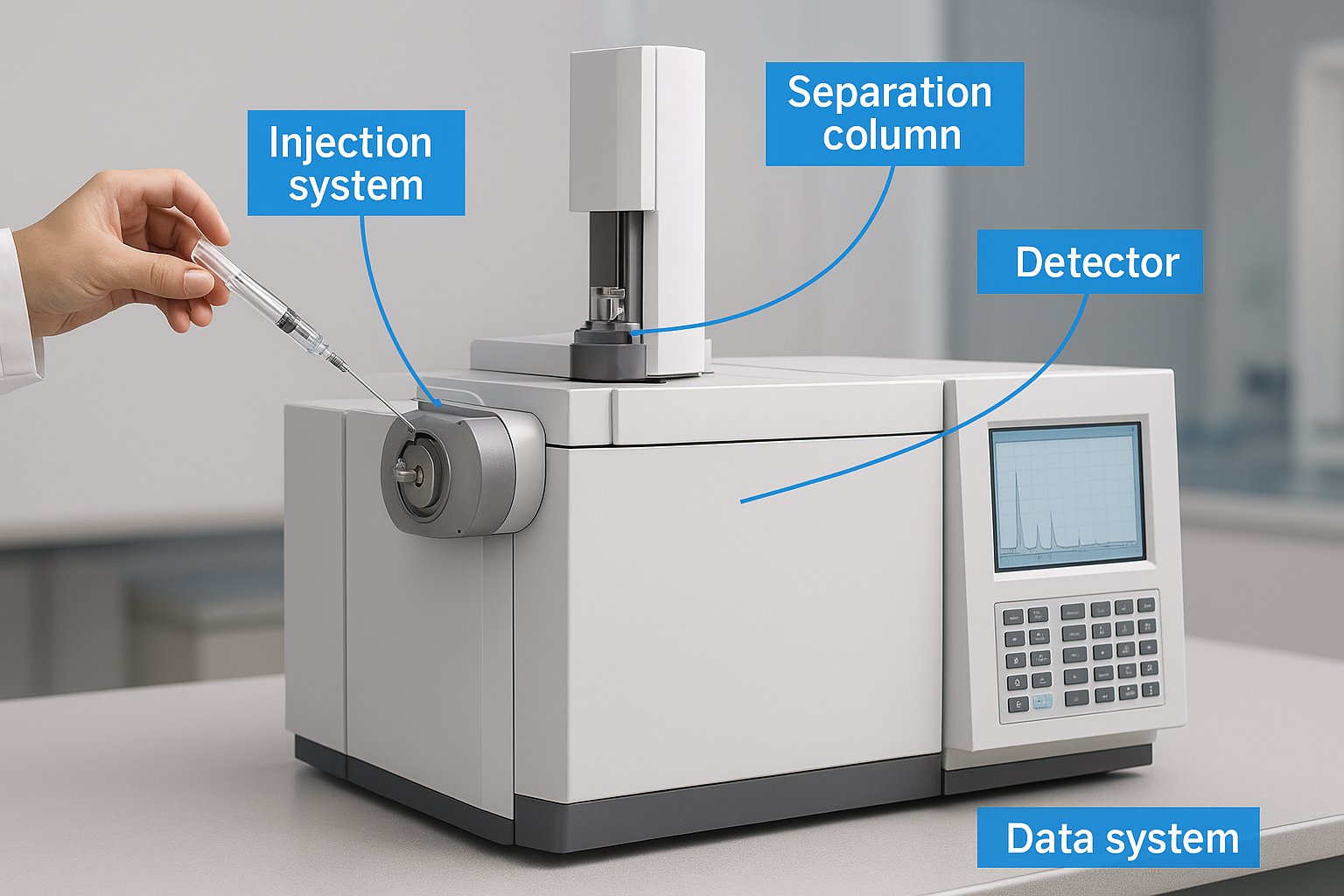

Main components of a gas chromatograph

Your gas chromatograph contains five essential systems that work together to separate and measure compounds in your samples. Each component plays a specific role in the analytical process, from initial sample introduction through final detection and data recording. Understanding what is gas chromatography means recognizing how these interconnected parts function as an integrated system. You need the injection system to introduce samples, the column to separate compounds, the detector to measure them, the carrier gas supply to move everything through, and the data system to record and interpret results. When you select or troubleshoot a GC system, you evaluate each component’s specifications against your analytical requirements.

Injection system and sample introduction

Your injection port serves as the entry point where liquid samples transform into vapor phase in milliseconds. You inject samples through a rubber septum using a microsyringe, and the heated port (typically 250°C to 350°C) instantly vaporizes your compounds. The system design matters because you need complete vaporization without thermal decomposition of sensitive compounds. Split injection diverts most of the sample to waste while sending a small fraction to the column, which works well for concentrated samples. Splitless injection delivers the entire sample to the column, providing the sensitivity you need for trace analysis.

Modern autosamplers handle injection reproducibility better than manual techniques, reducing variability between runs. You load multiple samples into the autosampler tray, program your sequence, and the system injects precise volumes consistently. This automation matters when you’re running overnight sequences or need to minimize analyst-to-analyst variation. Your injection technique affects peak shape and quantitation accuracy, making this component crucial for reliable results.

The separation column

Column selection determines separation quality more than any other factor in your GC system. Capillary columns dominate modern applications because they provide superior resolution compared to packed columns. You select columns based on their stationary phase chemistry, inner diameter, film thickness, and length. A nonpolar stationary phase (like dimethylpolysiloxane) separates compounds primarily by boiling point, while polar phases separate based on molecular interactions with functional groups.

Your column dimensions affect resolution and analysis time in predictable ways. Longer columns provide more theoretical plates and better separation but extend run times. Narrower internal diameters increase efficiency but reduce sample capacity. Film thickness controls retention, with thicker films holding compounds longer and improving separation of volatile materials. You match these specifications to your analytical challenges, choosing columns that resolve critical peak pairs while keeping total run time acceptable.

"The column’s stationary phase chemistry and physical dimensions directly determine which compounds you can separate and how long analysis takes."

Detector types and selection

Detectors convert separated compounds into electrical signals that your data system records as peaks. Flame ionization detectors (FID) respond to virtually all organic compounds, making them your workhorse choice for hydrocarbons and general organic analysis. You burn compounds in a hydrogen flame, which generates ions that create a measurable current. Thermal conductivity detectors (TCD) respond to any compound different from the carrier gas, including inorganic gases, but with lower sensitivity than FID.

Specialized detectors handle specific applications where selectivity matters. Electron capture detectors (ECD) provide extreme sensitivity for halogenated compounds and other electron-absorbing molecules, which makes them essential for pesticide analysis and environmental monitoring. Mass spectrometry detectors give you both quantitation and structural identification in a single run, though at higher cost and complexity than simpler detectors. Your detector choice depends on what compounds you’re measuring, required sensitivity levels, and whether you need universal response or selective detection.

Common applications and examples

Gas chromatography serves critical analytical needs across industries where precise chemical identification and quantitation drive product quality, safety, and regulatory compliance. You encounter GC applications everywhere from pharmaceutical laboratories testing drug purity to environmental agencies monitoring air quality. The technique excels when you need to separate and measure volatile and semi-volatile compounds in complex matrices, which makes it indispensable for materials characterization, contamination analysis, and quality verification. Understanding what is gas chromatography through real applications shows you how this technique solves practical analytical challenges across diverse fields.

Pharmaceutical and biomedical testing

Your pharmaceutical development and manufacturing processes rely on GC analysis for multiple quality control checkpoints. You use the technique to quantify residual solvents in drug substances, ensuring levels stay below ICH regulatory limits that protect patient safety. Active pharmaceutical ingredient purity testing identifies related impurities and degradation products that could affect efficacy or cause adverse reactions. Medical device manufacturers apply GC to characterize polymers, detect volatile additives in biomaterials, and verify sterilization efficacy through ethylene oxide residue analysis.

Biocompatibility testing programs incorporate GC methods when you extract medical devices and analyze leachables that might contact patient tissues. You identify and quantify plasticizers, antioxidants, and other additives that migrate from device materials under simulated use conditions. This data supports your regulatory submissions by demonstrating chemical safety and material characterization that meets FDA requirements for Class II and Class III devices.

Environmental monitoring and industrial quality control

Environmental laboratories use GC systems to measure volatile organic compounds in air samples, pesticides in water supplies, and polychlorinated biphenyls in soil contamination studies. You follow EPA methods that specify exact GC conditions, ensuring your results meet regulatory standards for environmental assessments and cleanup verification. Petroleum refineries apply the technique to analyze hydrocarbon mixtures in crude oil, gasoline, and other products, optimizing refining processes and confirming product specifications.

"Gas chromatography provides the separation power and sensitivity needed to meet stringent environmental and product quality standards."

Manufacturing quality control depends on GC analysis when you verify raw material purity, monitor production consistency, or investigate customer complaints about off-odors or contamination. You build methods specific to your materials, creating reference libraries of acceptable chromatograms that operators use for rapid go/no-go decisions on incoming materials and finished products.

Advantages, limits, and troubleshooting basics

Understanding what is gas chromatography means recognizing both its powerful capabilities and practical constraints that shape how you apply the technique. GC delivers exceptional performance for volatile compound analysis, but you face specific challenges that affect method development, sample compatibility, and day-to-day operations. Your success depends on matching technique strengths to your analytical needs while working around inherent limitations through proper method design and instrument maintenance. This section covers the advantages you gain from GC, the boundaries that constrain its application, and the troubleshooting skills you need when results don’t meet expectations.

Key advantages that matter in daily use

Gas chromatography provides superior resolution that separates complex mixtures into individual components other techniques struggle to resolve. You achieve baseline separation of compounds with similar structures, which matters when you need to quantify trace impurities in pharmaceutical materials or identify specific contaminants in environmental samples. Analysis speed gives you another practical advantage because most runs complete in 10 to 30 minutes, allowing high sample throughput for routine quality control work. This efficiency translates directly into faster decision-making and reduced analytical backlogs.

Sensitivity represents a critical strength when you work with limited sample quantities or need to detect compounds at parts-per-billion concentrations. Modern detectors respond to picogram-level amounts, which makes GC essential for trace analysis applications where sample availability constrains your options. Quantitative accuracy reaches levels that satisfy regulatory requirements, with properly calibrated methods achieving precision below 2% relative standard deviation for most applications.

"The combination of separation power, speed, and sensitivity makes gas chromatography your first choice for volatile compound analysis across industries."

Practical limitations to consider

Your sample compounds must be thermally stable and volatile enough to vaporize without decomposition, which excludes many polar, high-molecular-weight, or ionic materials from direct GC analysis. Derivatization expands your capabilities but adds method complexity and development time that might push you toward alternative techniques like liquid chromatography. Non-volatile compounds simply don’t work with GC, forcing you to choose different analytical approaches for polymers, proteins, or inorganic salts.

Column degradation affects long-term performance as repeated injections deposit nonvolatile residues that change retention characteristics or create active sites causing peak tailing. You monitor column performance through system suitability testing, replacing columns when resolution or peak shape deteriorates below acceptable levels. Sample matrix effects complicate analysis when you inject dirty samples containing particulates or high-boiling residues that contaminate injection ports and columns.

Common troubleshooting scenarios

Peak tailing indicates active sites in your injection port or column that adsorb polar compounds, creating asymmetric peaks that compromise quantitation accuracy. You address this by deactivating the inlet liner, trimming contaminated column ends, or switching to columns with better deactivation for your specific compounds. Baseline drift typically results from column bleed at high temperatures or carrier gas contamination, which you fix by reducing maximum temperature, replacing gas purification traps, or installing a new column.

Retention time shifts between runs signal temperature control problems or carrier gas flow inconsistencies that affect reproducibility. You verify oven temperature accuracy with independent thermometers and check flow rates using soap bubble meters or electronic flow meters to restore method consistency.

Bringing it all together

Understanding what is gas chromatography gives you analytical capabilities that directly impact your product development, quality control, and regulatory compliance efforts. You now know how the technique separates complex mixtures through differential partitioning, what system components control separation quality, and where GC delivers the most value across pharmaceutical, biomedical, and industrial applications. This knowledge helps you make informed decisions about when GC fits your analytical needs and when alternative techniques serve you better.

Your next step involves applying these principles to specific materials characterization challenges you face. Whether you need to verify material purity, identify contaminants, or meet regulatory testing requirements, the right analytical partner makes the difference between delayed projects and confident progress. Materials Metric provides specialized GC testing and materials characterization services that combine advanced instrumentation with expert interpretation, helping you accelerate innovation and achieve your development milestones.